How Welsh dairy has halved carbon emissions

© Hefin Richards

© Hefin Richards A Welsh family dairy has almost halved its carbon footprint from 1,447g to 809g of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilogram of fat- and protein-corrected milk, placing the farm within the top 5% of its milk pool.

Marc and Lucy Allison milk 300 autumn-calving cows at Sychpant Farm, near Cardigan, alongside Marc’s parents, John and Mair.

They say the improvement has been made by making small, incremental gains across the business in the past three years. This has brought their unit well below their milk pool average carbon footprint, which stands at 1,173g of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per kilogram of fat- and protein-corrected milk.

See also: How one Ayrshire dairy is cutting its carbon footprint

“We have done lots of little things and every year we tweak things in areas we think we can do better,” explains Marc.

Farm facts: Sychpant Farm, Cardigan

- Farming 210ha (519 acres)

- Growing 24ha maize, 2ha fodder beet, 8ha winter barley, 24ha winter wheat and the remainder grass

- Milking 300 Holstein cows

- Yielding 10,103 litres at 4.34% butterfat and 3.37% protein

- Selling milk to First Milk/Tesco

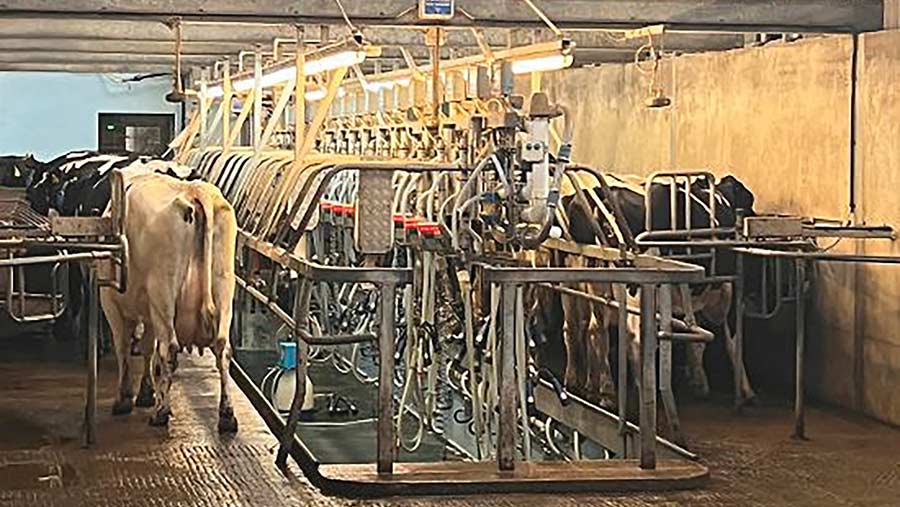

- Milking through a 16/32 swingover parlour

One of these areas is feed efficiency. Feed rate has fallen from 0.33kg/litre to 0.27kg. This has been achieved by focusing on growing more home-grown, good-quality feed, with 68% of the diet now made up of forage.

This has helped lift milk from forage from 3,711 litres to 5,093 litres.

This improvement has been helped by buying more land, enabling them to double the farm size, as well as paying attention to detail, such as pushing up food regularly.

Previously, maize was bought in from a grower in Shropshire, but now, 24ha (59 acres) of the crop is grown on-farm.

It is established under film to create a microclimate and offset the challenges brought about by farming at 152m above sea level on predominantly north-facing land.

This has helped negate transport emissions and allows the crop to be harvested early in September, which avoids soil damage in a wet autumn. It helps improve starch content, with last year’s crop averaging 37% starch (see “Forage analysis for 2022”).

Grass is undersown in first-year maize to protect the soil over winter and provide an early bite of spring grass for in-calf heifers.

The Allisons operate a multicut silaging system, aiming to cut leys of ryegrass and red clover four times annually.

Better use of slurry has helped lower nitrogen use from 184kg/ha to 126kg/ha.

Slurry is applied to crops using a trailing shoe at 45cu m/ha, with the grazing platform receiving dirty water during any dry periods of weather.

Last year, 4ha (10 acres) of fodder beet was grown to counteract rising feed prices and has replaced beet pulp. This yielded 400t and was chopped and mixed into the milkers’ total mixed ration.

The move has also helped lift constituents, which are important given the Allisons are on a cheese contract, explains the Allisons’ nutritionist, Hefin Richards of Rumenation Nutrition Consultancy.

© Hefin Richards

Roofing the main silage clamp has improved daily ration consistency, too. “It is an exposed farm and driving rain comes in off the sea. The clamp was catching so much water and it was hard to feed accurately day-to-day. [Some days,] the ration was like soup,” he says.

Milkers are fed grass silage, maize, wheat and barley and brewers’ grains or blend, which is regularly reformatted to match forage supply (see Milkers’ ration box below).

Soya has been replaced in the total mixed ration (TMR) this year by a blend of protected rape expellers, methionine and rape.

The TMR is fed alongside a 16% concentrate, which is fed to yield in the parlour up to a maximum of 4kg a head.

Milkers’ ration for winter 2022/23

- 32kg grass silage

- 13kg maize silage

- 0.5kg chopped wheat straw

- 8kg chopped fodder beet

- 6kg brewers’ grains

- 1.75kg urea/enzyme-treated wheat

- 1.75kg rolled barley

- 1.5kg crimped maize

- 3.75kg blend (comprising high-energy, protected rape expellers, rape, non-palm fat, methionine, acid buff and minerals)

Ration based on freshweight a head. 68% of this diet was grown on farm.

Transition of calving pattern

Switching from all-year-round to autumn calving four years ago has helped the Allisons reduce the age at first calving from 30 months to 24 months, which has also helped lower their carbon footprint.

All replacements are born in the first eight weeks of the 16-week block. Lucy says: “When it comes to getting the heifers in-calf, it is a lot simpler.

“We start serving on the third week in October and we put Afimilk [heat detection] collars on the heifers.”

Calves will be expected to hit 100kg ready for weaning at 10 weeks. “I want calves to grow into the winter; for us to hit two-year calving, it’s an important growth stage,” adds Marc.

Cows graze from March. Heifers calve outdoors while cows graze standing hay for four weeks before being brought inside and transitioned to a dry cow diet four weeks pre-calving.

© Hefin Richards

Cows are milked three times a day from September until April. This helps shorten each milking time to 2.5 hours while cows are in peak milk, benefiting cow health by reducing standing times and improving udder health, says Marc.

Heifers are genomic-tested with the highest-ranking animals based on predicted transmitting ability (PTA) for constituents and health traits.

They are then served to sexed semen, alongside the best cows that come back bulling in the first eight weeks of the block.

The remainder of the cows are served to Limousin, Charolais and British Blue, while heifers are mated to Angus for easy calving.

Herd health

Good preventative herd health is underpinning good fertility, milk production and low antibiotics use at Sychpant. All these are key drivers for lowering carbon emissions.

The herd is vaccinated for leptospirosis, bovine viral diarrhoea, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and rotacorona, with all cows receiving a calcium bolus after calving.

Cows are housed in sand-bedded cubicles in a well-ventilated, spacious, bird-proof shed. Last season, mastitis rates averaged only six cases in 300 cows and there were just half a dozen cases of milk fever.

“If the cows are happy and comfortable, that makes our job a lot easier because we are dealing with low levels of disease. We haven’t had a displaced abomasum for three years,” he says.

Future improvements

This season, first-lactation heifers will be housed separately from cows in a newly renovated 60-cubicle shed, to prevent bullying.

“Cows are doing 11,000 litres and heifers are doing 8,000 litres; if we can improve that, it is going to be a winner,” he explains.

Next, Marc is considering growing hybrid rye. This is a high-fibre and low-cost forage perfect for feeding dry cows to replace expensive straw, explains Hefin.

However, the decision will not be straightforward: “It depends on if we have the acres with the new Welsh nitrate vulnerable zone constraints. If [growing hybrid rye] costs me maize, then it won’t be worth it.

“The government haven’t really thought it through, because all they are doing is making farmers buy our feed down the M4 corridor, when we can grow it.”

Forage analysis for 2022 |

|||

|

|

First cut |

Second cut |

Maize |

|

Dry matter (DM) % |

26 |

32 |

33 |

|

Digestibility value |

74 |

72 |

73 |

|

Metabolisable energy (MJ/kg DM) |

11.75 |

11.45 |

11.7 |

|

Protein % |

14.8 |

15.3 |

8.2 |

|

Neutral detergent fibre (NDF) % |

41 |

43 |

37 |