Regenerative approach builds resilience for 1,750-cow herd

© Shirley MacMillan/MAG

© Shirley MacMillan/MAG Building resilience into the business by growing his own cereals and having a rolling stock of 27,000t of silage is part of Neil Baker’s move to regenerative agriculture.

In fact, one of his new key performance indicators at Rushywood Farm, Somerset, is to have six months’ worth of forage on hand.

“We would get short of forage and have to buy in. We used to be constantly booking feed to fill gaps and either buying some feed or selling some cows,” he says.

See also: Dairy farms turn to forage to manage spiralling costs

Neil admits, however, that having forage in stock ties up working capital: It requires cash to make the silage and storage to hold it. He has doubled clamp capacity since 2017, when he would have just 7,000t in stock for 2,100 cows.

“Because there is so much money involved, we are monitoring silage monthly and keeping tighter control on waste, whereas 10 years ago we would wing it and just make a phone call for food,” he says.

“We are far more resilient now, but I’m not sure how to balance it with flexibility.”

Farm facts: Rushywood

- 1,750 milking cows

- 11,300 litres a cow sold

- 1,800 heifers

- 250 beef cattle

- 34km hedges

- 1,334ha (3,296 acres) cropped

- 500kW anaerobic digester for manure and crop waste

Forage sufficiency

As a fourth-generation farmer, Neil wants to see his farm be viable for the seventh, eighth and even ninth generation of Bakers. “I farm in partnership with my mother and three children, and 35 staff.

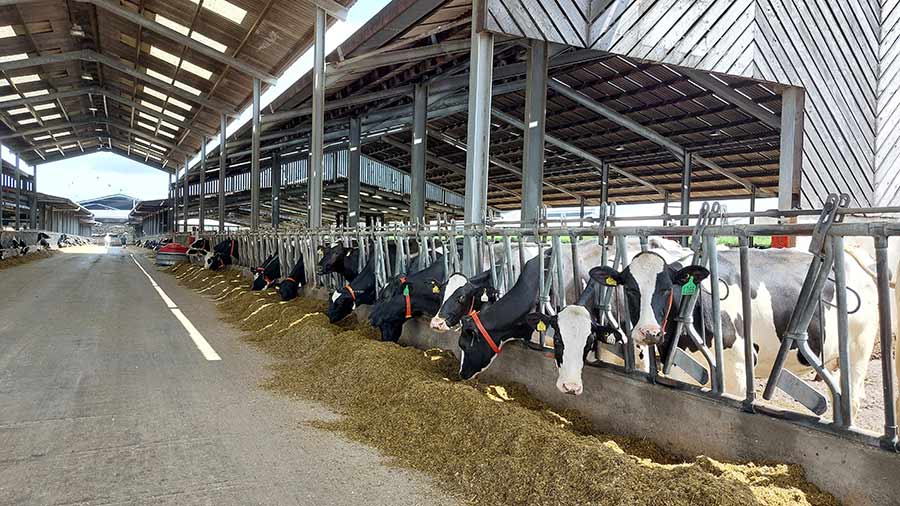

“Our herd is fully housed, including heifers, we do our own forage, and grow half of our concentrates. We now feed an 80% home-grown ration.”

Neil has moved away from growing monocultures and now sees muck as a useful resource.

Formerly running a grass and maize farm, he had tried growing lucerne, red clover and soya, but struggled as the farm was too wet. Now he grows wheat, plus pea and barley wholecrop, and only buys proteins.

“We have come away from leaving bare maize stubble in October to harvesting maize in September and getting a cover crop in for winter. We are trying to increase biodiversity by growing two species in a field.

“The thing I learned is that we are producing 10-20% more crops – not less – with regen. If you get it right, it’s a virtuous circle.

Halving inputs

“We have reduced pesticide and fertiliser use. We can definitely cut fertiliser use in half without a reduction in crop yields, but how to reduce pesticides and other sprays is a bit of a dark art.

“Even herbicides kill insects and we wreck the microflora under the soil. We are hypocritical at the moment as we are on a journey and are not doing it all; but our target is: Can we halve inputs?” he says.

All dung, slurry and waste silage goes into the farm’s anaerobic digester. The resulting digestate (about 30,000cu m/year) is used as a fertiliser.

“We have a lot of manure and need a lot of manure-spreading windows. In the past, our target was to empty the lagoon onto maize.

“Now we have 450 acres (182ha) of barley and peas, and 800 acres (323ha) of wheat, and they are good to spread with muck,” he says.

As Neil only owns 323ha (800 acres) of his farmed land and says it is not possible to buy more, he works with 12 different neighbours on farming agreements.

“Without access to land, we would be back to 500 cows,” he adds.

Neil Baker was speaking at the recent regenerative farming event Down to Earth, which was held on his Somerset farm.